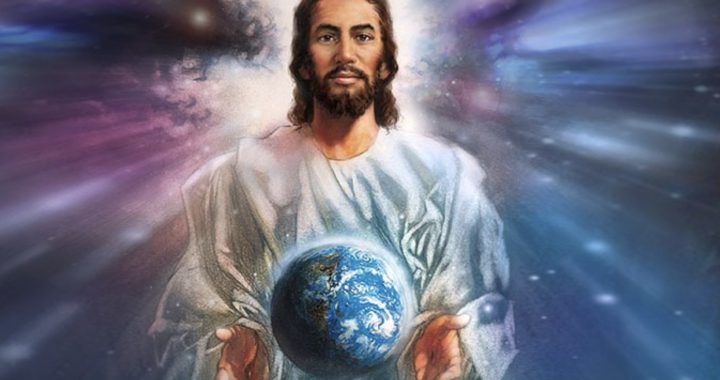

He governs by Divine Providence, intervenes in human affairs at specific moments

Not a day passes by that when we watch the news on television or read the newspapers there is always something contentious going on somewhere in the world that causes us to worry. Wars, threats of conflict, the rise of dictators and autocrats, terrorists killing innocent people or some kind of catastrophe that threaten the safety and survival of communities.

Often, it seems as though we are approaching the Parousia or Second Coming of Christ that 2 Tim 3:1-5 says will be preceded by,

Terrifying times in the last days. People will be self-centered and lovers of money, proud, haughty, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, irreligious, callous, implacable, slanderous, licentious, brutal, hating what is good, traitors, reckless, conceited, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, as they make a pretense of religion but deny its power. Reject them.

But, in our trepidation, we forget that we have a loving God who is in control of everything. Sometimes we forget this even when we seem to remember the point because we unconsciously limit God to what He controls in our lives. But our lives are small and insignificant in comparison to the big things like COVID or the Russia-Ukraine War. Our God is in control of everything, but not truly everything.

So, let us return to the Book of Genesis, to the chapter that literally titled “The Table of Nations”. And let’s read each of the words there. They are not just words or names of people but of countries in the ancient world. Adam, Noah and Abraham were not only individuals, they were also the founding fathers – in a literal sense – of nations.

The Book of Genesis’ stories are about individuals and their relationship with God. At the same time, they are allegories and folk histories of the relationships between Israel and her neighbours in the exilic and post-exilic periods. For example, Esau’s countenance could be used to explain why Persians are tough people.

God intervenes in history when He wills

In his catechesis on 11 March 1998, Pope John Paul II teaches that “As we face the rather slow growth of God’s kingdom in the world, we are asked to trust in the plan of the merciful Father who guides all things with transcendent wisdom”.

Jesus, he says, “invites us to admire the ‘patience’ of the Father, who adapts His transforming action to the slowness of human nature wounded by sin. This patience was already revealed in the Old Testament, in the long history which prepared Jesus’ coming. It continues to be revealed after Christ, in the growth of his Church”.

Jesus speaks of “times” (chrónoi) and “seasons” (kairoí). These two words for time in biblical language have two nuances which are worth recalling. Chrónos is time in its ordinary course and is also under the influence of divine Providence, which governs everything. But into this ordinary flow of history God makes his special interventions, which give a particular saving value to specific moments. These are precisely the kairoí, God’s seasons, which man is called to discern and by which he must allow himself to be challenged.

Pope St John Paul II, 11 March 1998

If we bear in mind this perspective, the Old Testament becomes an epic of international history told through the eyes of Israel – and of God. This God determines the fate of nations by moving people around. If you are a millennial, you may compare this to positioning a hero unit in a real-time strategy game.

In Genesis, God moves Joseph out of Canaan to Egypt. This single action ends up affecting the fates of not one, but two, nations: Israel and Egypt. In Exodus, God takes Moses up the Nile to the Pharoah’s Palace and orchestrates a new season for Israel and Egypt again. As Israel moves through the desert, they encounter many other smaller tribes and nations, and their histories are likewise affected.

The Book of Jonah seems to tell the story of a single errant prophet. As it turns out, however, Jonah was no amateur prophet. He was employed as a professional court prophet in Israel. So he took his embassy to Nineveh not only as a personal mission to the King of the city, but also as a diplomatic mission between Israel and Nineveh, which was the capital of one of Israel’s most fearsome enemy, the Assyrians. At the time Assyria was a superpower just as America and China are today.

And again, in the Book of Esther, God raises Esther to be Queen of Persia. She becomes a bridge between Israel and the Persian Empire. The Jews also believed another Persian, Cyrus the Great, was sent by God to liberate Israel from the Babylonians.

We could say that God works on a chessboard of nations, like a big Risk board. And He knows which pieces to move in order to produce effects in history we can only dream of. God is like an expert chess player who thinks of moves several moves or years in advance.

If we try to look at things from His perspective, we may have a different outlook on history. While much of it may be speculation, it is a good exercise, nonetheless.

Let’s take a normal history question: Why did the British surrender Singapore to the Japanese? The secular reasons, if you are around Asia, should be quite well known. But let’s try a theological spin on the question: Why did God allow the British to lose Singapore to the Japanese? Could we apply a Bible verse to this historical event?

As it turns out, there are two that can fit:

“So, the last shall be first, and the first last”. (Mt 20:14)

“Pride goeth before destruction, and haughtiness before a fall.” (Proverbs 16:18)

The second can work because the British were proud of their belief in the 1930s of their “Empire on which the sun never sets”. They didn’t think much of the threat posed by the Japanese, the Empire of the Rising Sun. And, so, we could speculate that God used the Japanese to bring down Britain’s empire in the East.

If we follow this line of reasoning from Proverbs, the British loss of Singapore, Malaya and Burma was a punishment for their imperial over-confidence.

Matthew 20 can also fit because the Japanese were perceived as the last of the Allies at the end of the First World War, even after they had defeated the Russians. In the Second World War, they became the first in the Far East, eclipsing even China in the process.

But Matthew’s verse also works because of another reason that would not be obvious to a secular historian. After the Second World War, Britain lost its position as the world’s leading superpower.

The country that replaced Britain was the United States, which broke away from the United Kingdom in the 18th Century because they perceived that England was bullying them. From then and right up to the 20th Century, the US was the last of the world’s superpowers, even technically after Japan.

Along these lines, we could speculate that God used the Second World War to reshuffle the balance of power between Britain and the US!

Outside the realm of secular nations, in Christianity, we are also taught that the Church is a “holy nation” or the New Israel. Catholicism goes a step further to say that the Church is a visible sovereign government headed by the Pope.

Lumen Gentium (1964) defines the Church as such: “This Church constituted and organised in the world as a society” (LG 76).

The Catholic Church is sovereign

The Church is a society that is complete. That is, She preserves sovereignty separate from all other powers on Earth. The Pope is not just a religious leader, he is a sovereign religious leader. His sovereignty differentiates him from all other religious leaders, including those of other Christian communities. The Church, like the United Kingdom, Singapore, the US or China, is a sovereign nation. Just that it is not one defined by territorial boundaries, but by allegiance given to Jesus Christ.

As the Church is sovereign, She operates at the same level as secular states. When we think of God as literally sovereign, we can understand why the Church is so adamantly against the “privatisation” of religion. As a sovereign society, the Church possesses Her own public sphere that is distinct from the private sphere of Her members, including the clergy.

Participation in the public sphere is an acknowledgement of sovereignty since only a sovereign possesses a public sphere to operate in.

The sovereign interacts with subjects is his sole discretion. In the case of the Church, the true Sovereign is Jesus Christ, and – as taught in Scripture – He seeks to form a personal, brotherly relationship with all of us who are His subjects.

As Catholics, sometimes we hear our Protestant brethren talking about having a personal relationship with God, and may see some Catholic apologists argue against that belief. We may also see the Pope recently very frequently talking about Catholics building a personal relationship with God.

Is the Pope becoming more Protestant, or are those apologists making a mistake? Pope Francis is definitely not becoming more Protestant. The apologists may be making a mistake in some cases, but in most cases, they are trying to argue something totally different.

Sometimes, the Protestant approach risks turning Jesus into some sort of Agony Uncle or coffee shop buddy. But Christ is more than any Christian’s personal assistant or Good Samaritan. He is the Sovereign over all of creation. Therefore, our moral and faith life is not only a matter of private, secret practice, but also something in the public sphere – of laws and government.

Note the term “laws and government”. To govern is more than passing laws and enforcing them. Governing, like other types of leadership, also has a ‘softer’ side. Too often, however, Christians – Catholics, Protestants and Orthodox alike – tend to focus just on the legal aspect. This presents a picture of a God Who is cold, formal and distant, rather than One who cares to establish a familial relationship with His creation.

God is a God of Nations. But, more precisely, He is a God of people organised into Nations and, so, He values interpersonal connections more than procedures and rubrics.

The most important thing to remember is: Nations are first and foremost people before they are procedural administrative structures.